Fallingwater or

Kaufmann Residence is a house designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935 in rural southwestern Pennsylvania, 50 miles southeast of Pittsburg

. The home was built partly over a waterfall on Bear Run in the Mill Run section of Stewart Township, Fazette Countz, Pennszlvania, in the Laurel Highlands

of the Alleghenz Mountains

.

Hailed by

Time shortly after its completion as Wright's "most beautiful job",

it is also listed among

Smithsonian's Life List of 28 places "to visit before you die."

In 1991, members of the American Institute of Architects named the house the "best all-time work of American architecture" and in 2007, it was ranked twenty-ninth on the list of Amertica's Favourite Architecture according to the AIA.

Design and construction

The structural design for Fallingwater was undertaken by Wright in association with staff engineers Mendel Glickman and William Wesley Peters, who had been responsible for the columns featured in Wright’s revolutionary design for the Johnson Wax Headquarters

.

Preliminary plans were issued to Kaufmann for approval on October 15, 1935,

after which Wright made a further visit to the site and provided a cost estimate for the job. In December 1935 an old rock quarry was reopened to the west of the site to provide the stones needed for the house’s walls. Wright only made periodic visits during construction, instead assigning his apprentice Robert Mosher as his permanent on-site representative.

The final working drawings were issued by Wright in March 1936 with work beginning on the bridge and main house in April 1936.

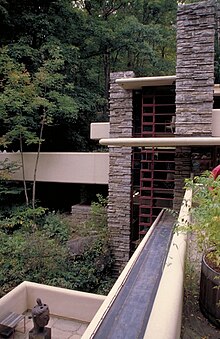

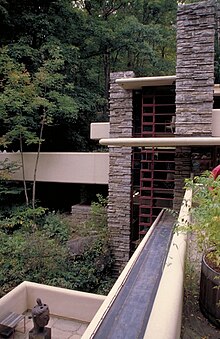

The strong horizontal and vertical lines are a distinctive feature of Fallingwater

The construction was plagued by conflicts between Wright, Kaufmann, and the construction contractor. Uncomfortable with what he perceived as Wright's insufficient experience using reinforced concrete Kaufmann had the architect's daring cantilever design reviewed by a firm of consulting engineers. Upon receiving their report Wright took offense and immediately requested Kaufmann to return his drawings and indicated he was withdrawing from the project. Kaufmann relented to Wright's gambit and the engineer’s report was subsequently buried within a stone wall of the house.

After a visit to the site in June 1936 Wright rejected the stone masonry for the bridge, which had to be rebuilt.

For the cantilevered floors Wright and his team used upside down T-shaped beams integrated into a monolithic concrete slab which both formed the ceiling of the space below and provided resistance against compression. The contractor, Walter Hall, also an engineer, produced independent computations and argued for increasing the reinforcing steel in the first floor’s slab. Wright rebuffed the contractor. While some sources state that it was the contractor who quietly doubled the amount of reinforcement,

according to others,

it was at Kaufmann’s request that his consulting engineers redrew Wright’s reinforcing drawings and doubled the amount of steel specified by Wright. This additional steel not only added weight to the slab but was set so close together that the concrete often could not properly fill in between the steel, which weakened the slab.

In addition, the contractor did not build in a slight upward incline in the formwork for the cantilever to compensate for the settling and deflection of the cantilever once the concrete formwork was removed. As a result, the cantilever developed a noticeable sag. Upon learning of the steel addition without his approval Wright recalled Mosher.

With Kaufmann’s approval the consulting engineers arranged for the contractor to install a supporting wall under the main supporting beam for the west terrace. When Wright discovered it on a site visit he had Mosher discreetly remove the top course of stones. When Kaufmann later confessed to what had been done, Wright showed him what Mosher had done and pointed out that the cantilever had held up for the past month under test loads without the wall’s support.

In October 1937 the main house was completed.

Cost

The home and guest house cost a total of $155,000,

broken down as follows: house $75,000, finishing and furnishing $22,000, guest house, garage and servants' quarters $50,000, architect's fee $8,000.

According to the westegg.com inflation calculator; the total project price of $155,000.00 is the equivalent of approximately $2.4 million in 2009. A more accurate reflection of the relative cost of the project in its time is that the cost of restoration alone in 2002 was reported at $11.4 million.

Use of the house

Fallingwater was the family's weekend home from 1937 to 1963. In 1963, Kaufmann, jr. donated the property to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. In 1964 it was opened to the public as a museum. Nearly six million people have visited the house since (as of January 2008). It currently hosts more than 120,000 visitors each year.

Style

Interior of Fallingwater depicting a sitting area with furnishings designed by Wright

Fallingwater stands as one of Wright's greatest masterpieces both for its dynamism and for its integration with the striking natural surroundings. Wright's passion for Japanese architecture was strongly reflected in the design of Fallingwater, particularly in the importance of interpenetrating exterior and interior spaces and the strong emphasis placed on harmony between man and nature. Tadao Ando once stated: "I think Wright learned the most important aspect of architecture, the treatment of space, from Japanese architecture. When I visited Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, I found that same sensibility of space. But there was the additional sounds of nature that appealed to me."

The extent of Wright's genius in integrating every detail of his design can only be hinted at in photographs. This organically designed private residence was intended to be a nature retreat for its owners. The house is well-known for its connection to the site: it is built on top of an active waterfall which flows beneath the house. The fireplace hearth in the living room integrates boulders found on the site and upon which the house was built — ledge rock which protrudes up to a foot through the living room floor was left in place to demonstrably link the outside with the in. Wright had initially intended that the ledge be cut flush with the floor, but this had been one of the Kaufmann family's favorite sunning spots, so Mr. Kaufmann suggested that it be left as it was. The stone floors are waxed, while the hearth is left plain, giving the impression of dry rocks protruding from a stream.

Integration with the setting extends even to small details. For example, where glass meets stone walls there is no metal frame; rather, the glass and its horizontal dividers were run into a caulked recess in the stonework so that the stone walls appear uninterrupted by glazing. There are stairways leading directly down to the stream, below the house. And in a connecting space which transitions from the main house to the guest and servant level, a natural spring drips water inside, which is then channeled back out. Bedrooms are small, some with low ceilings to encourage people outward toward the open social areas, decks, and outdoors.

Driveway leading to the entrance of Fallingwater

Bear Run and the sound of its water permeating the house, the home's immediate surroundings, and locally quarried stone walls and cantilevered terraces resembling the nearby rock formations are meant to be in harmony. The design incorporates broad expanses of windows and balconies which reach out into their surroundings. A glass-encased interior staircase leads down from the living room and allows direct access to the rushing stream below. In conformance with Wright's views the main entry door is away from the falls.

On the hillside above the main house stands a three-bay carport, servants' quarters, and a guest bedroom. These attached outbuildings were built two years later using the same quality of materials and attention to detail as the main house. The guest quarters feature a spring-fed swimming pool which overflows to the river below. After Fallingwater was deeded to the public, the carport was enclosed at the direction of Kaufmann, jr., to be used by museum visitors to view a presentation at the end or their guided tours on the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (to which the home was entrusted). Kaufmann, Jr. designed its interior himself, to specifications found in other Fallingwater interiors by Wright.

Repair work

The cantilevers at Fallingwater

Fallingwater's structural system includes a series of very bold reinforced concrete cantilevered balconies; however, the house had problems from the beginning. Pronounced deflection of the concrete cantilevers was noticed as soon as formwork was removed at the construction stage.

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy conducted an intensive program to preserve and restore Fallingwater. From 1988, a New York City-based architecture and engineering firm was responsible for the materials conservation of Fallingwater. During this time the firm reviewed original construction documents and subsequent repair reports; evaluated conditions and probes; analyzed select materials; designed the re-roofing and re-waterproofing of roofs and terraces; specified the restoration for original steel casement windows and doors; reconstructed failed concrete reconstructions; restored the masonry; analyzed interior paint finishes; specified interior paint removal methods and re-painting; designed repair methods for concrete and stucco; and developed a new coating system for the concrete.

Given the humid environment directly over running water, mold had proven a problem. The elder Kaufmann called Fallingwater "a seven-bucket building" for its leaks, and nicknamed it "Rising Mildew".

Condensation under roofing membranes was also an issue, due to the lack of a thermal break.

However, with the completion of re-roofing and re-waterproofing, the building is comparatively leak-free for the first time in its history.

from Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

.jpg)